By Marcia Mota-Kerby, Educational Psychologist

Every day, educators are navigating social and emotional complexities, supporting children’s wellbeing, fostering inclusion, and responding to diverse needs within ever-changing contexts. Schools are not only spaces of learning but also places of safety, belonging, and emotional support for pupils and their families. Within this dynamic landscape, compassion is not an option – it is a necessity. It is an internal motivational process that can transform the school culture, restore connection, and strengthen communities from within.

What Is Compassion?

Compassion, as defined by the psychologist Paul Gilbert (2019) is “a sensitivity to suffering in self and others, with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it.”

It involves two key components:

- Engagement – noticing and tuning in to distress (in ourselves or others).

- Action – taking wise, supportive steps to help reduce that distress.

Unlike empathy, which focuses on recognising and connecting with another person’s emotions, compassion adds the motivation to help. It engages courage, wisdom, and emotional regulation, skills that can be developed individually and collectively.

The Flows of Compassion

In Gilbert’s model, compassion exists in three interconnected flows, each are essential for wellbeing:

- Compassion for Others – our ability to notice when someone else is struggling and to respond with care and understanding.

- Compassion from Others – our capacity to accept care and support when we are struggling.

- Self-Compassion – how we respond to ourselves during challenging moments, whether triggered by external events (like a specific incident), internal experiences (such as emotions, thoughts, or feelings), or a sense of personal failure.

In a school context, these flows form a dynamic network that shapes the emotional health and wellbeing of the entire school community.

- When teachers offer compassion to students – by listening, adapting, or holding space for mistakes – they help pupils overcome challenges, low self-confidence, shame and self-criticism, and develop trust.

- When staff receive compassion from colleagues and leaders – through empathy, care, and shared understanding, they are better able to sustain their own wellbeing.

- When individuals practise self-compassion, they can recover more effectively from setbacks and maintain perspective in challenging situations

A compassionate school culture nurtures all three flows, recognising that everyone, students, teachers, leaders, and families, needs both to give and receive compassion to flourish.

Why Compassion Matters in Schools

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that compassion is not merely a moral ideal but a scientifically supported approach that enhances wellbeing and learning across educational contexts.

- Neuroscientific research shows that compassion engages neural systems linked to soothing, caregiving, and affiliation, mechanisms that help balance the brain’s stress and threat responses (Klimecki et al., 2013; Lutz, Greischar, & Davidson, 2004). In essence, compassion activates the very systems that foster emotional regulation, safety, and connection. For schools, this has powerful implications: when both staff and pupils experience a sense of psychological safety and belonging, the conditions for learning, curiosity, creativity, and motivation naturally thrive.

- Research by Kristin Neff (2003) and Christopher Germer (2018) shows that self-compassion reduces anxiety, promotes resilience, and helps individuals cope and recover from challenges, essential qualities in both teaching and learning. Similarly, Jennings and Greenberg (2009) found that educators who cultivate emotional awareness and compassion create classrooms with lower stress levels, better relationships, and improved student outcomes.

- From an organisational perspective, Huppert and So (2013) identified compassion and empathy as core components of psychological wellbeing in schools, while Roeser et al. (2013) demonstrated that teachers trained in mindfulness and compassion-based practices experience less emotional exhaustion and greater professional efficacy.

Ultimately, compassion is not an “add-on”; it is the foundation of a psychologically safe, inclusive, and healthy-performing school culture.

If compassion is embedded into school life, what does this look like?

- Classrooms that emphasise connection before correction – where behaviour is understood as communication and where mistakes are treated as learning opportunities.

- Leadership teams that model emotional openness, support staff wellbeing, and promote shared reflection.

- Policies and procedures grounded in fairness and understanding, balancing accountability with empathy. Compassion in education thrives when supported by clear expectations and healthy boundaries, enabling care that is empathetic, balanced, and sustainable for both staff and students.

- Staffrooms where colleagues check in on one another, and vulnerability is met with care and kindness.

- Children and young people who feel safe, seen, and valued.

Embedding compassion throughout school life lays the foundation for a more relational and responsive approach, one that aligns naturally with the principles of humanisation in education.

Humanisation in Education: From Systems to Relationships

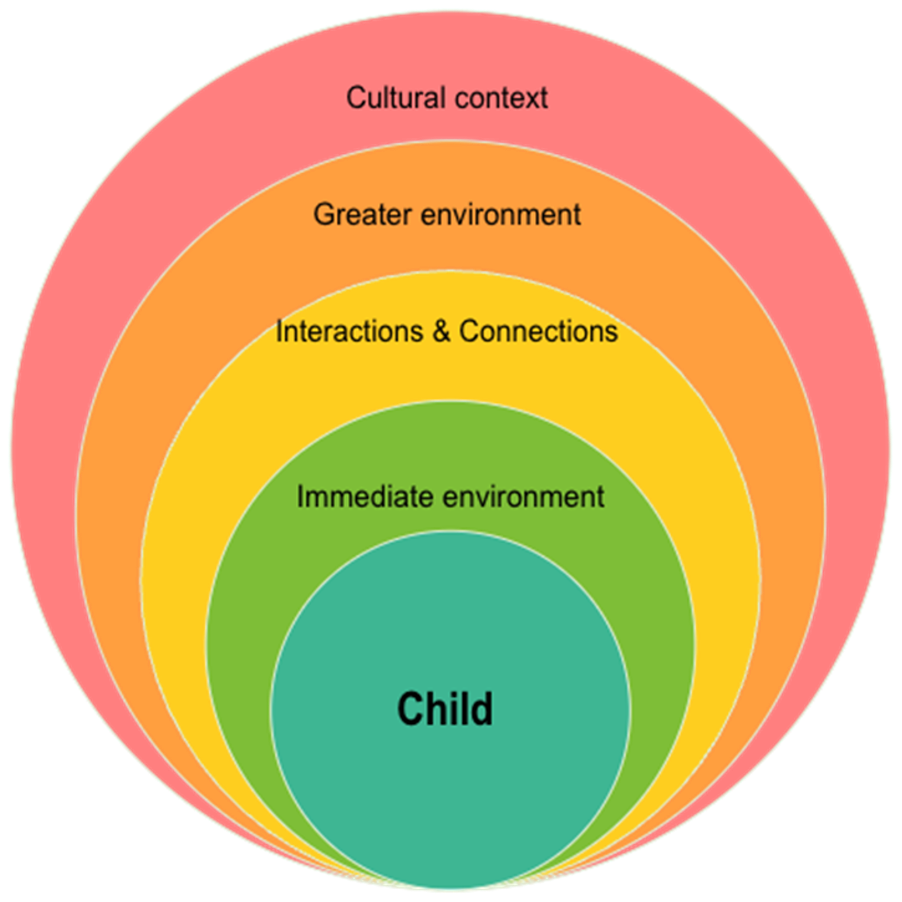

To humanise school services means putting relationships, understanding, and empathy at the centre of how we work with children, families, and colleagues. It involves recognising that behaviour, emotions, learning, and wellbeing are interconnected, and that behind every challenge lies a story and a narrative that deserves to be understood.

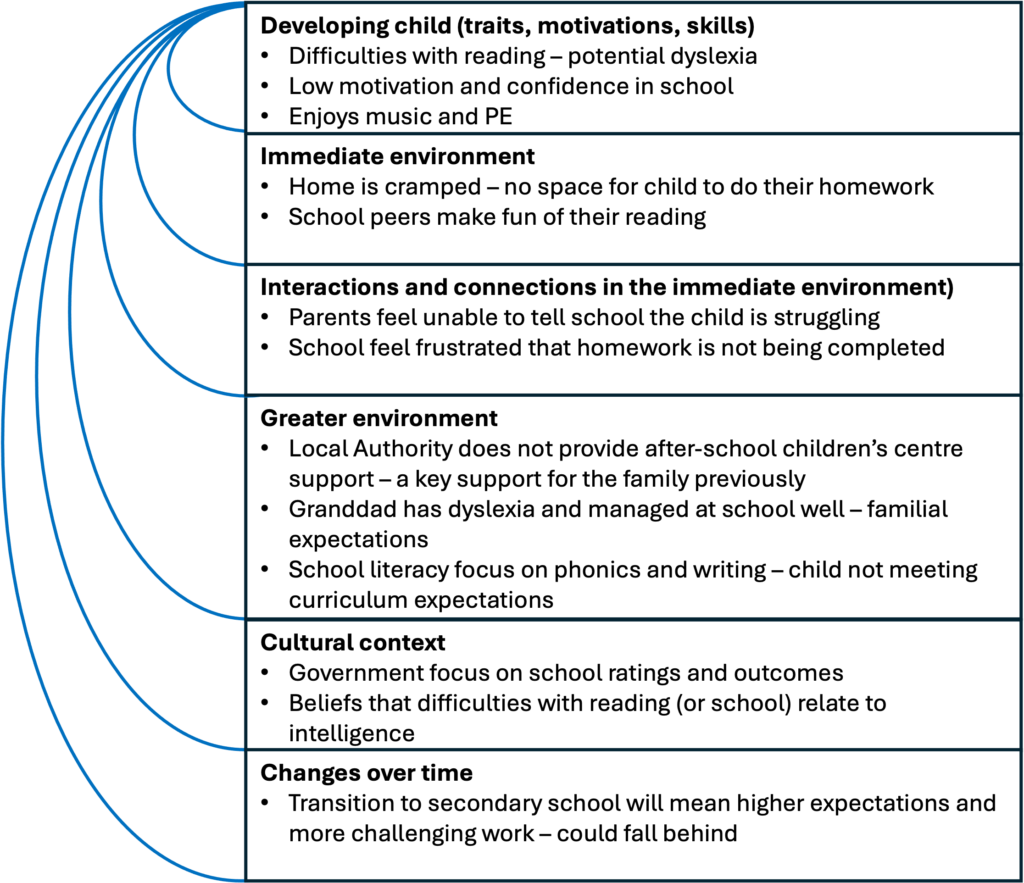

In a compassionate school, systems are designed to support people rather than manage problems. Humanisation starts with a shift in mindset: moving from “What’s wrong with this child?” to “What’s happened to this child?”, and ultimately to “What does this person need to feel safe, connected, and ready to learn?”

When schools embrace this approach, every layer of the organisation, from classroom practice to leadership decision-making, begins to reflect compassion in action:

- Inclusive and relational support systems prioritise the child’s context and voice, recognising that progress depends as much on belonging and trust as on academic targets (Roffey, 2016).

- Pastoral and behaviour policies emphasise repair over punishment, using restorative conversations and emotion coaching to help pupils learn from difficulties and build resilience (McCluskey et al., 2019).

- Staff wellbeing structures create psychologically safe spaces for reflection, supervision, and peer support, acknowledging that educators cannot pour from an empty cup (Herman et al., 2020).

- Partnerships with families are grounded in listening, empathy, and collaboration, strengthening community trust and shared responsibility for children’s wellbeing.

- Leadership practices model compassion through transparency, curiosity, and care, valuing people’s emotions and experiences alongside performance indicators (Seligman, 2011; Roffey, 2021).

When services are humanised, schools evolve from systems of compliance into communities of care. Interactions become grounded in respect, acceptance, fostering trust and cooperation. In such environments, children feel safe to learn, teachers feel empowered to teach, and relationships not routines, form the heartbeat of the school.

Cultivating Compassion: A Call to Action

Cultivating compassion is not about adding another initiative to an already full plate, it is about changing the plate itself. It begins with small acts: taking a moment to listen, to pause before responding, to cultivate a non-judgmental approach, and assume positive intent. Over time, these micro-moments form the foundation of a compassionate culture.

Developing compassion is a skill. It requires intentional practice: slowing down, listening deeply, and responding with care even when time is short. Schools can nurture this through:

- Staff training in compassion focused and values-based approaches. Building awareness of one’s own emotions and responses enables educators to remain calm, and grounded, especially under pressure.

- Reflective supervision and peer support. Providing regular spaces for staff to reflect on challenging situations helps normalise and validate emotional responses within an intrapersonal context, reduce isolation, and strengthen professional resilience.

- Curriculum initiatives that teach empathy, perspective-taking, and emotional literacy. Embedding compassion-based learning into PSHE, citizenship, and pastoral care encourages students to understand and manage emotions constructively.

- Leadership that promotes values and connection as much as compliance and outcomes.Compassionate leadership models openness, listens actively, and ensures that wellbeing is woven into school development priorities.

Compassion is courage in action. And when it flows through every level of a school, it truly becomes a superpower, one capable of transforming education from the inside out.